Junko Tabei, first woman to summit Everest in 1975

To be asked to give a talk about one of the best kept secrets in the mountaineering world a few years ago during my own Everest journey was a real privilege and researching the life of Junko Tabei opened my eyes to the life of this incredible diminutive lady who simply wouldn’t take no for an answer. When I mentioned to people that I was giving a talk about her, their stock answer would be ‘who?’ which is a travesty. We can all learn so much from her.

Junko Tabei: 22/09/1939 - 20/10/2016

Born in 1939 and the youngest of 7 children including 5 female siblings, later in her childhood she felt that her Father would have liked another boy having heard that he had said ‘a girl again’ when she was born. Maybe this instilled in her a want and a will to succeed at whatever she did prove to her Father that it really doesn’t matter what gender you are but how you deal with your life that counts.

She was a very poorly child, often succumbing to pneumonia, so for her to go onto be a world class mountaineer was a surprise to all of her family. Her first taste of great heights came on a school trip when she was 10 years old to scale the 1915m peak, Nasu Dake. She found it incredibly hard and made friends with the fact that ‘only you can move your legs, all you have to do is to put one foot in front of the other and you would get there’. This is something that I say to my clients on expeditions which to an adult seems utterly obvious, as a 10-year-old it is hugely insightful.

Moving into her teenage years, she had to make a deal with her Father that she would definitely have children in the future but he had to let her finish her education first as in those days it was rare for girls to go to secondary school and even rarer for girls to go to university. Moving from the fresh air and freedom of the countryside to the hustle and bustle of the Tokyo for university, she felt trapped and suffered from bouts of depression until she discovered a climbing club and met with a young lady called Sasau, who became her best friend and climbing partner. They were a force to be reckoned with and respected within the very male dominated climbing scene of the time. Sadly, Sasau lost her life in a climbing accident which shook Junko to her core. She knew she had to carry on and take the memory of Sasau with her.

During her climbing days with her best friend, she spotted a rather handsome gentleman and accomplished climber called Masanobu. He would inhabit the best bunk on the train, not through selfishness or arrogance but because everyone else knew that he had earned the right to be there. They skirted around each other for a while before serendipity called. On a climb with Sasau, they crested a ridge to find Masanobu waiting to welcome them with a desert of sorbet he had made out of a tin of fruit and the snow. Junko knew then that he was the man for her.

‘We all have encounters in life that either brighten our future or dampen our dreams’ and on meeting her soon to be mentor Kiochi Yoko-o, she knew this was a positive step forward. She would only climb with people she knew would push her skills and abilities, so having Sasau, Masanobu and Yoko-o around her. The climbing scene in Tokyo was small and the number of women involved even smaller so when she had thoughts of climbing to greater heights, many said that it couldn’t be done, that she wouldn’t be able to pull it off. Little did they know then what this lady, small in stature but big in tenacity, would be capable of.

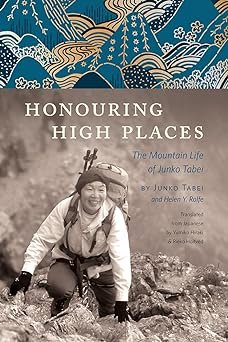

Setting up an all-female climbing group was the first step on a huge journey to the summit of Everest. Not that she had any ambitions for those great heights to begin with but after a successful ascent of the 7000m peak Annapurna III in 1970 she knew that greater heights were possible. Annapurna III was a big learning curve for Junko not only climbing wise but also as an Expedition Leader of a team of hugely different personalities and ambitions. She put together the team, and with the help of fellow team-mates, sourced funding and equipment for this first all-female expedition to the Himalayas. However, this expedition was not without its troubles. Coming back from a successful summit where only 2 of the 12 team members stood on the summit, including Junko, a very honest and direct account of the expedition was written. As she mentions in her book, Honouring High Places which is well worth a read, if you have 12 people telling a story you are going to have 12 different versions of that story. The book was heavily criticised for its frank nature, but she did not see the point in drawing a fluffy picture of something that was ultimately so hard and told it as it was. I quite agree.

When she came back from Annapurna III and her thoughts turned to putting together an expedition to Everest, her now husband Masanobu requested that if she was going to be away for such a long period of time that he had a part of her to stay with him so their first child, a daughter called Noriko, was born in 1972. During this time Junko was worked hard to put together the first all-female expedition to climb Everest. Back in those days only 1 team were granted a permit to climb Everest each season. As permits for 1973 and 1974 were already granted, they were finally given the go ahead to climb in 1975. The Ministry of Tourism in Nepal had offered other mountains such as Manaslu (8163m) however only Everest would do.

No female had stood on top of Everest to date so putting together an all-female team was a huge deal for Junko, finding women who would play various parts of the team and fit in nicely together. Their expedition was during one of the worst economic down turns in Japanese history so finding sponsors was as a tough call as finding suitable teammates.

‘Everest – I’d love to go but….’ I found it difficult to hear people crush their dreams with the word ‘but’ she said. Once again, I totally agree. We all have great ambitions and the only thing that stops the dream from happening is the lack of action. She was not going to let the words ‘but’ or ‘no’ stop her from achieving what she knew was possible.

In December 1974, with sponsorship and a team in place, she left her husband and daughter in Tokyo and embarked on a long journey to the roof of the world. This journey was fraught with internal wrangling’s amongst the team and dangers on the mountain. Leaving Jiri to start the long trek into Everest Base Camp were 14 female team members, 1 Doctor, a film crew and 600 porters in early Spring of 1975 no-one could have predicted that, chosen by their team leader Eiko Hisano, only Junko and her climbing Sherpa, Ang Tsering, would stand on top on 16th May, uttering the words ‘Oh, I don’t have to climb anymore’.

During the long months of acclimatisation and gear hauling up the mountain the group dealt with altitude sickness, bad weather, injury and a life-threatening avalanche which buried Junko and her teammates at Camp 2, 6400m. They had moved their camp spot a little higher up the glacier when Junko saw how much climbing ‘tat’ had been left by a previous Spanish group. That move nearly cost them their lives. The tenacity of Junko and her fellow climbers and Sherpas then ensured a swift recovery from serious injury and the cobbling together what kit they had to safely keep on climbing. They successfully continued on from an incident which would have sent most teams scuttling off the mountain in retreat.

Junko learned many lessons once again from that big climb, from team management to not leaving her own climbing tat on the mountain. Something that at the time and above 8000m she thought nothing of as it was the way of the era (and sadly, too often still is in this era too) and latterly she organised mountain clear ups and highlighted the detriment of leaving rubbish in formerly pristine places.

Junko was hailed a hero on her return to Japan and quite rightly so too. She surpassed many an expectation, pushing not only her own boundaries but the boundaries of those around her. She was a leading light in encouraging anyone, no matter their age or gender, to achieve more, whatever their more may have been. She was not only the first female to stand on top of Everest but latterly also the first female to complete the 7 summits and continued to climb high and hard as well as leading expeditions on many a mountain.

To sum up the magnitude of the life of this woman of many climbing and social firsts is a tough call in 1500 words so I will encourage you to read her book, Honouring High Places, I promise you won’t be disappointed. Not only is it a great story but also resonates with so many parts of modern life from her observations that she was judged by her height, gender and appearance rather than her ability to climb, to her tenacity to get the job done in the face of adversity.

I pulled out so many quotes from the book when I have previously presented Junko to an audience and this one quote fits the bill for my Nepal 2025 as a reminder of just how far we have come since Junko’s time in 1975 and although we still have a way to go, I am hoping that by taking an all-female DofE team to walk in Junko’s footsteps and learn more about this truly pioneering lady, they will leave away with a sense of achievement which will pave the way for themselves and other women in the future.

‘Near the time of our climb, the United Nations declared 1975 as International Women’s Year at a world conference held in Mexico City. I heard afterwards that the audience at the conference surged with applause when news of the first female success on Everest was reported. Whether I wanted it to be or not, our climb became a symbol of women’s social progress.’

Junko Tabei – Honouring High Places. Also the first woman to complete the 7 summits.